I was recently asked what most men want in life. It was a broad question, but one that I contemplated quite a bit. It seems that each individual desires something different—money, status, a sense of happiness, peace, marriage, children, and strong, dependable relationships. After a few nights of thoughtful reflection and delving into my personal philosophy, I arrived at this conclusion.

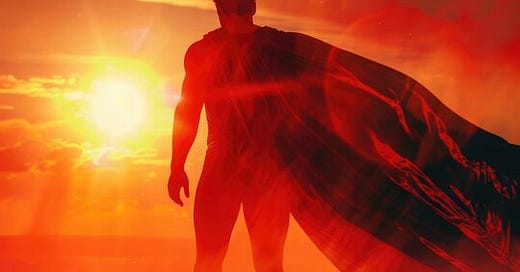

All men need to feel like the hero — if not for their lifetime at least every now and then.

Maybe this need is hidden in the unconscious. Perhaps he knows but can’t quite articulate it. But to my mind, most men—at least those with some self-awareness—derive their sense of worth from providing, protecting, building, and problem-solving, regardless of scale, however big or small. In the broadest, most generous terms, he privately relishes the role of the white knight. This is clear in the boardroom on Wall Street, where men are hailed as heroes after closing a deal. It's also true in a halfway house, where men talk about the guy who went cold turkey as if he earned a Purple Heart.

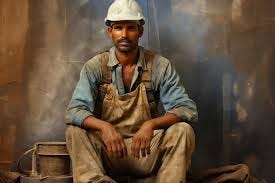

It doesn’t require a cape or transcendent power to play the role. First responders and soldiers deserve approval, but it also extends to those who string power lines, drill for oil, build houses, and harvest food—men who supply society with the essentials it needs to function.

We also should value the men who set a positive example, a role model if you will, of competence and compassion — the husbands, the brothers, the fathers, the guy who reads a bedtime story to his adolescent son, helps him ride a bike without training wheels or constructs the impossible Lego toy.

The thing is, most men don’t need a badge, applause, awards, honors, or some outward show of fawning gratitude or praise.

A nod of approval is good enough.

The Hero: Big or Small

Call it insecurity, uncertainty, or even fear, but deep down, men need this sense of approval from the community and the people they love. He may show this in simple and unpretentious ways — carrying your heavy suitcase, washing your car — or something more beneficent, like being at your side to protect you from the big bad world out there.

Whatever the reason, it does not matter how big or small the act, men crave to be the hero.

Without culturally accepted avenues for heroism, a market for unapproved, antisocial alternatives will emerge; a disturbing sense of worth or misguided masculinity through crime or violence, or apathy — playing video games, using illegal substances, or watching porn in his parents’ basement.

Men are struggling. Statistics bear this out. Men are lagging socially, academically, and in mental health. Suicide is the leading cause of death for all men under 40. Deaths of despair, they call it. Nine out of 10 homeless individuals are men. Eight of ten of those incarcerated are men.

It goes on and on. Without acceptance, a sense of purpose or value, a sign of approval or grace, many men will slip off the dangerous cliff of uselessness.

Aurora

On July 20, 2012, James Harris, a lonely and delusional 24-year-old man entered the Century 16 theater in Aurora during a midnight screening of The Dark Knight Rises. He was armed with a shotgun, a semi-automatic rifle, and a handgun. At 12:30 a.m., Harris threw two smoke canisters into the theater and opened fire. Chaos ensued. In the end, 12 people lay dead, and 70 more were wounded.

Among the dead were three young men: Matt McQuinn (27), Alexander Tevis (26) and Jonathan Blunk (26). When Harris opened fire, each of the young men instinctively dove on top of their girlfriends to shield them from the hail of bullets.

All three girlfriends lived.

Approval, acceptance and appreciation

Historically, men’s roles in groups, like tribes or families, depended on being accepted as capable and reliable. Rejection could mean ostracism, which back in the day was a survival threat.

Today, that ancient instinct still lingers. Acceptance from peers, partners, or even themselves can feel like confirmation they’re measuring up—not just to external standards but to their internal ones. Men often tie self-esteem to external approval, though it varies by individual and culture. It’s not universal, but it’s a pattern. Being “enough” in the eyes of others can quiet that nagging doubt about inadequacy.

On the flip side, it’s not all about insecurity. Acceptance can also just feel good—it’s a signal you’re valued, respected, or understood. For some men, it’s less about proving something and more about connection. Think of a guy with his buddies, the unspoken “you’re one of us” vibe matters more than any grand declaration.

While not universally true for every man, the idea that "men just want to be a hero" taps into a common psychological theme where many feel a deep desire to be seen as capable and competent, to be seen as problem solvers, and, just as important, to be equanimous while doing so.

His desire to be seen as a hero taps into some deep currents of human nature— philosophy, psychology, and even mythology all have something to say about it. At its core, this impulse might stem from a need for meaning and purpose. Thinkers like Friedrick Nietzsche pointed to the "will to power" — not just domination, but the drive to assert one’s existence, to matter in a chaotic world. Being a hero, even momentarily, is a way to transcend the mundane, to feel like one’s life has agency.

Then there’s the social angle. Aristotle saw humans as inherently communal, defining us by our roles in the polis. Heroes get praise, admiration, and status — things that signal you’re valuable to the tribe. Evolutionary psychology might back this up. Standing out as brave or selfless could’ve meant better mates, more allies, and higher survival odds. Even today, that wiring lingers—men (and people generally) crave recognition because it’s baked into how we’ve thrived.

Mythology amplifies it too. Joseph Campbell’s "hero’s journey" isn’t just a story template; it’s a mirror for our psyches. Men grow up on tales of Odysseus, Beowulf, or even Spider-Man, where struggle and triumph define

worth. Sometimes, wanting to be the hero is wanting to live a story that’s epic, not just a footnote.

But it’s not constant. "Sometimes" fits because the urge ebbs and flows — tied to moments of insecurity, opportunity, or crisis. French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre called it a flight from "nothingness" — when life feels aimless, playing the hero is a grab at purpose. Not every guy’s out to save the world daily. It’s more like a latent itch, scratched when the stakes align.

Does every man feel this? Hard to say—culture, upbringing, and temperament manifest in contingent ways. Some might chase it through quiet duty, others through loud bravado.

Men are born to dream of being the hero. If you have one in your life, chances are he wants to be yours.

A smile of acknowledgment will do.

###

Who is your hero? Why?

Jim Geschke was inducted into the prestigious Marquis “Who’s Who” registry in 2021.

Great article, Jim! I see this need in my own family members, and need to acknowledge it more than I do. Thanks for the reminder!

Very prescient and , as usual, thought provoking. Nice work Jim. 47 days.....