When my son Andrew was 10 years old, just about four months before Y2K, my wife (Elaine) and I got a phone call from his school’s principal. It seemed there had been a playground incident involving Andrew and another boy, and we were summoned to receive a report of the details.

The principal was a schoolmarmish 50-something woman, with horn-rimmed glasses and the requisite button-down sweater. She greeted us with a friendly but firm smile. The details were thus: the other boy punched Andrew over who was to retain possession of a ball. (We found out later it was a sucker punch.) Andrew responded by giving the young ruffian a rather thorough beat-down, tearing the boy’s shirt in the process. Because of the affront, Andrew was given a 3-day suspension and was to pay for the torn shirt.’

“Who threw the first punch?” I asked. The other boy was the answer. “So, he’s being punished for defending himself?” Affirmative. She explained the school had a zero-tolerance rule for fighting, regardless of the instigation.

“So what was he supposed to do?” I asked.

Her response was as follows:

“He was supposed to lie down, curl up in a ball and wait for a playground supervisor to intervene.”

She said it with a straight face. I must have looked at her like an alien because Elaine squeezed my leg under the table as if to say, “Don’t … I know what you’re thinking, and I agree … but don’t.” I managed somehow to smother my anger.

But deep inside I was proud. He defended himself and defied a silly and unrealistic school rule. When Andrew got in the car, I reassured him … “You’re not in trouble. Consider it a holiday. What would you like to do?”

We never paid for the torn shirt.

Boys are simple creatures

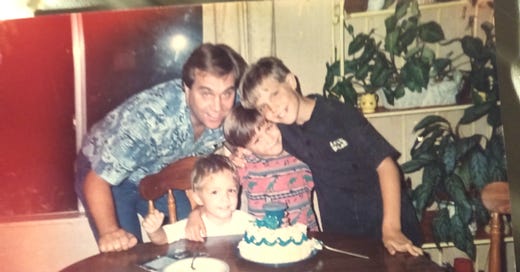

I assume Andrew’s aggression was hard-wired in his DNA. Male aggression. King-of-the-Hill type stuff. He was my second born, three years younger than his brother Chris and three years older than his younger brother Nicholas. Therefore, I can only speak as a father of boys, which, I assume, is decidedly different than my friends who had daughters.

Boys, I learned, are simple creatures. Low maintenance, I’d argue. It doesn’t take much to keep them happy. Video games, explosions, trucks, bone-jarring hits in football, dinosaurs, belching, taking the piss out of each other (insults), funny movie lines … and food. Lots and lots of food.

Growing up, boys exhibit certain behaviors that a parent must deem acceptable, such as dressing in unmatched colors, collecting disgusting odors, or deciding they could make that 10-foot jump only to fail and do a faceplant on the pavement. Others are not. Bullying in any form was not tolerated, nor was disrespectful behavior toward an adult or lying. As for stealing that last piece of pie left unmarked in the refrigerator, that was up for debate.

Mostly, however, you end up throwing up your hands in acknowledgment that inexplicable behaviors were simply the product of XY chromosomes, testosterone and 100,000 years of ape-like evolution.

For instance, there was a time when we left an expanse of space unguarded in the living/family room when we moved the furniture to have the carpet cleaned. In the boys’ eyes — they were 15, 12 and 9 at the time — they saw a WWE wrestling opportunity. A brawl ensued, and after 30 minutes the carnage included 10 stitches, a splint, blood stains on the carpet, two loose teeth, and an assortment of bruises, cuts and abrasions.

They were breathless and happy as clams. This, I learned, was natural. Somewhere around age 12 (give or take) boys go brain-dead and only emerge from the shutdown when the rewards supersede the risks.

Then again, some never grow up.

“You don’t raise heroes, you raise sons. And if you treat them like sons, they’ll turn out to be heroes, even if it’s just in your own eyes.” –Walter M. Schirra, Sr.Fatherhood

Fatherhood

Let’s get serious for the moment.

I was never provided instructions about parenting practices, such as role modeling, responsibility, life skills, communication, and conflict resolution. I believed, for better or worse, in lived experience. I learned by trial and error to cope, to accept failure simply as a way not to do something, and to persevere when life throws the inevitable curveball. I hoped for my boys to be humble yet strong when the situation called for it, to act honorably when a crisis arose, to practice self-discipline, and to be equanimous.

Victorian poet Rudyard Kipling got it right in the first two lines of his immortal poem “If” …

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

The poem lists various rights of passage to manhood: honesty, pride, endurance, strength, and humbleness. It ends with a resolution ……..

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!

If I were to offer an abridged version of “If,” it would be this:

Do the right thing when nobody is looking and never, ever give up.

Modern Masculinity

How has the role of masculinity changed since I was a young man? How important are risk-taking and seeking adventure? Should we teach the values of being a provider and protector, and the virtues of strength (physical, mental, emotional)? What is our role in the family? In the community?

On the surface, that has changed somewhat. Society has morphed. Expectations for men have been downplayed, degraded, and even marginalized. However, social expectations should not be the defining factor in a young man’s life. Strength with integrity is a duty as a father, I believe, and no less important now than it was 50 years ago as I entered adulthood.

It goes beyond the roles of provider and protector. It encompasses emotional stability, active participation in a child's life, and setting the best positive example. Teaching politeness and manners never goes out of style. Neither does giving respect and being humble. Most of all, don’t expect any “thank yous.” They won’t be coming.

Five factors to being a good father include, but are not exclusive to ….

Ethics: Demonstrate honesty, integrity, and respect for others.

Conflict: Show your son how to resolve conflict, hopefully peacefully and respectfully. But be ready to stand your ground to do what is right.

Personal Responsibility: This is critical: to learn the importance of taking personal responsibility for their actions and accepting the consequences of all decisions. Be accountable. Know that doing what’s right isn’t always popular.

Feedback: Offer guidance and correction. Be stern. But always say “I love you.”

Mental and Physical Health: Prioritize your well-being. Always show them the best version of yourself.

It never ends. There is no time limit to being a Dad. You don’t suddenly “age out” or run into a time limit. Fatherhood requires patience and a willingness to listen, learn and grow.

And the willingness to tear some shirts along the way.

“A boy needs a father to show him how to be in the world. He needs to be given swagger, taught how to read a map so that he can recognize the roads that lead to life and the paths that lead to death, how to know what love requires, and where to find steel in the heart when life makes demands on us that are greater than we think we can endure.” –Ian Morgan Cron

###

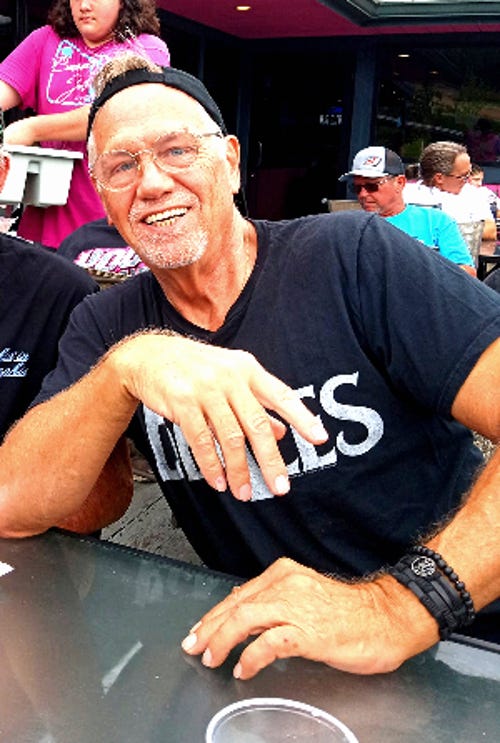

Jim Geschke was inducted into the Marquis Who’s Who Registry in 2021.

Thanks for writing this. As the dad of a single female, I'm sure our fathering was a bit different. I hope your health is getting near 100%? Merry Christmas, Bro!

Jim,

Your essay on boys is profound.

I will be reading and absorbing it many times.

I admire your powerful leadership as a father

in showing your son

that we never accept an order

to lie down in the fetal position!

Even if it comes from someone in power.

We defend ourselves from attack!

We refuse to pay any penalty for doing so!

We reward the heroic act!

WOW what a great lived parable

for raising brave men.