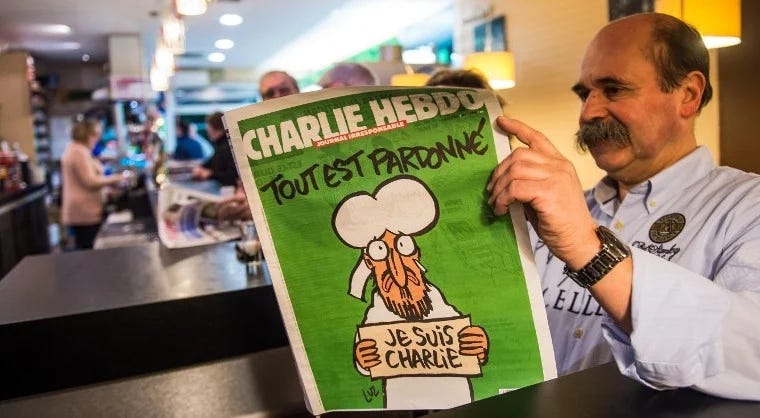

"Je suis Charlie!"

It has been 10 years -- Jan. 7, 2015 -- since the Islamic attack on the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. Not much has changed since.

On January 7th, 2015 two brothers, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, entered the offices of Charlie Hebdo, a satirical weekly magazine known for its provocative cartoons, including those depicting the Prophet Muhammad. Armed with assault rifles and rocket launchers, they opened fire, killing 12 people, including nine journalists and cartoonists, two police officers and a receptionist. Eleven others were injured.

The brothers shouted "Allahu Akbar" (“God is great”) during the attack, and later claimed to be acting on behalf of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

A massive two-day manhunt followed, involving thousands of police officers. Police tracked the Kouachi brothers as they fled into the offices of Création Tendance Découverte, a signage production company located in the Dammartin-en-Goële, a town outside of Paris.

After a nine-hour standoff, the Kouachi brothers emerged from the signage company with guns blazing and were subsequently shot and killed.

Global Outrage

The attacks shocked the world and sparked widespread condemnation of terrorism and a global outpouring of support for freedom of expression. On January 11, about two million people, including more than 40 world leaders, met in Paris for a rally of national unity. Millions more joined demonstrations across France and throughout the world.

The phrase Je suis Charlie (“I am Charlie”) became a unifying cry of support at rallies and on social media. Charlie Hebdo continued with the publication, and the following issue ran 8 million copies in six languages, compared to its typical print run of 60,000 in French only.

The attacks raised significant debate about the limits of free speech, the role of satire, and the challenges of combating extremism.

Protest … then blowback

The magazine's long history of publishing controversial and satirical cartoons often targeted religious and political figures. This led to previous threats and attacks, including a firebombing of the Charlie Hebdo offices in 2011.

Two days after the Charlie Hebdo attack, Amedy Coulibaly, an associate of the Kouachi brothers, killed four hostages and a police officer in a Parisian kosher supermarket. The jihadists continued their attacks throughout the year and beyond, with France as the primary target. The deadliest attacks took place on November 13, 2015, when a series of coordinated strikes at six locations in central Paris killed 130 people, including 89 at a heavy metal concert.

For once, the free world seemed to rally to support the victims. At the time, the crime was seen as extremist action and drew universal condemnation. But only for an instant.

Before long, a slew of American literati changed its tune, capitulating to political predilection. According to the chattering class, Charlie Hebdo had crossed the critical line of “proper” taste. Their cartoons were a not-so-subtle form of blasphemy. They purposely offended Islam, all Muslims, and their sensibilities. The publisher was Islamaphobic, bigoted actually, “punching down” on the world’s population of 1.5 billion Muslims.

In other words, Charlie Hebdo was “asking for it.”

“Islamaphobia … a word created by fascists, used by cowards to manipulate morons.” — Christopher Hitchens

Many of these commentators had probably never heard of Charlie Hebdo until the attack. They knew nothing about the magazine’s anarchic humor. In publishing cartoons of the prophet, they were practicing the liberté, égalité, fraternité at the heart of the Republic, celebrating the French ideal of laïcité, or secularism. In short, Charlie Hebdo expressed what they thought of the political class and religion, to treat all sacred values equally deserving of satire.

In other words, they were exercising the West’s most fundamental right … the right to free speech.

Religious Satire

The tradition of satirizing religion was also the province of English-speaking writers dating back to the 14th century. Geoffrey Chaucer frequently targeted the corruption of the Church in the Canterbury Tales, a series of stories of 24 travelers who made the pilgrimage from London to Canterbury to honor the anniversary of the martyred Sir Tomas Becket nearly two centuries before.

While the work is not an outright attack on religion itself, it exposes the foibles and failings of individual pilgrims pretending to be pious but who are more interested in personal gain and worldly pleasures than in serving God and their parishioners.

Perhaps the most strident attack on the Christian faithful was penned by Jonathan Swift, known best for his mockery of European aristocracy in the novel Gulliver’s Travels. In 1729, he published the famous essay “A Modest Proposal,” a juvenalien satire of the British Crown and Anglican Church. He proposed, some thought seriously, to solve the Crowns’ problem of Irish poverty by “eating babies.”

Religious satire, however outrageous, is centuries old. But the targets were never the theology or doctrine of religion, but those who would pervert or corrupt the canons of faith.

“Je suis Charlie!”

The attacks occurred amidst a global rise in Islamic extremism, with groups like al-Qaeda and ISIS carrying out numerous terrorist attacks worldwide. They have been marginalized but replaced by groups like Hamas, Hezbollah and the Muslim Brotherhood. The names have changed, but the goal is the same — global jihadism — with the deadliest of consequences.

The attacks also ignited debates about the limits of free speech, particularly over religious and cultural sensitivities. It highlighted the dangers of extremism, the importance of freedom of expression, and the challenges of living in a pluralistic society.

If we are to continue as a free society, we must challenge the institutions and factions that would limit or eliminate the calls for social change, however offensive they may be.

To that I say “Je suis Charlie!”

###

Jim Geschke was inducted into the Marquis Who’s Who in 2021.