A Brief History of Satire

From Chaucer to Vonnegut, a satirist may make readers laugh, but they also want to make them think.

Satire is as old as folly. There have always been abuses of power, political corruption, church and religious transgressions and flawed customs. And right behind them, there often has been a mischievous observer with an acerbic wit and sharp pen.

Satirists use the palliative of humor to address the ills and errors of their time. It is a form of social commentary that exposes flaws and injustice in hopes of educating humanity and improving the social order.

Humor is generally a central component. But it is not the sole purpose. A satirist may make readers laugh, but they also want to make them think.

Of course, the intent hasn’t always achieved the desired result. Throughout history, edgy or audacious satire incited shock (see: “A Modest Proposal” below), or so offended the target that the provocateur was publicly rebuked, sometimes even temporarily or permanently silenced.

Today we call it Cancel Culture.

The humor can range from “laugh out loud” funny … to a quiet, bemused chuckle. However, darker humor may prompt a shuddering, cover-your-mouth “I shouldn’t be laughing, but I am” response, especially anything viewed as in bad taste or offensive.

To the satirist, this is gold. As British comic Ricky Gervais says, “just because you’re offended doesn’t mean you’re right.”

Point taken.

Satirists have questioned the social order since antiquity, and done so in many languages. But with all due deference to Erasmus, Kafka, Voltaire, Gogol and many more, this treatise is limited to a few of the most influential who plied their trade in the English language.

Geoffrey Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales

Scholars often credit the first satire written in the English language to Geoffrey Chaucer (b 1343-1400). A Medieval polymath, Chaucer was a literate man of many talents and life pursuits. Most importantly, he was a survivor. Chaucer was only four-years-old when the Black Plague decimated half the population of Europe in 1347.

Chaucer’s exposure to all aspects of English feudal society led him to understand, analyze and critique its rigid social caste system. Although he wrote in many forms (poetry, prose, etc.), his masterpiece came late in life (between 1390 and 1400) with the writing of The Canterbury Tales.

The Canterbury Tales comprises a series of “framed stories,” that is, stories within a story. The main plot features 30 members of English society – all from disparate levels of the feudal hierarchy – who collectively embark on a pilgrimage from London to Canterbury (65 miles) to visit the shrine of Sir Thomas Becket1 at Canterbury Cathedral.

Chaucer sets the fictional plot in motion in a Prologue as the “pilgrims” meet at Harry Bailly’s Tabard Inn in Southwark, a suburb of London. Before their departure, Bailly (The Host) challenges the travelers: whoever tells the best story on the journey will win a feast in his/her honor at his pub … and sends them on their way.

The Prologue introduces the 30 pilgrims, with each character described in scrumptious detail. These are people from all walks of feudal life: the saintly Knight, a Merchant, the lowly Miller, the deceitful Pardoner, a wife of Bath and many others.

Each tale is told in third-person narrative style, all written Middle English. Some are written in prose, while others are spoken in heroic couplets2. All tales carry a moral lesson. Chaucer’s genius is in the telling; every pilgrim speaks in the voice of his/her place in society. Thus, the lowly Miller is shamelessly vulgar, while the Knight speaks in chivalric tones.

The Pardoner’s Tale is a perfect example, exposing Chaucer’s distaste for the corruption of the Catholic Church. The Pardoner is a particularly loathsome cur. He tells the other pilgrims about his occupation—a combination of itinerant preaching and selling of “indulgences” (Papal pardons) and religious relics to the poor and indigent. His sermon is always the same: Radix malorum est Cupiditas, or “greed is the root of all evil.” After each sermon, he breaks out his bag of relics to sell to the innocents — which he readily admits are fake. He then begins his story …

The Pardoner’s Tale is about three drunken “rioters” (lowlifes) who, upon witnessing the funeral procession of a friend, vow to “kill Death.” The rioters strike out to find Death, but instead come upon a mysterious stranger who directs them to a tree laden with treasure.

Very quickly they forget about Death, and plot to divvy up the bounty. In the end, the rioters end up killing each other in a three-way double-cross. The satire, of course, lies in the greed and treachery of three drunks and exposing the hypocrisy of The Pardoner himself.

Jonathan Swift: Gulliver’s Travels and “A Modest Proposal”

Gulliver’s Travels

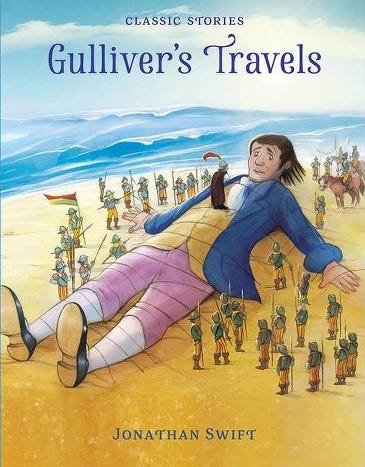

In the 18th century, famed cleric and satirist Jonathan Swift used satire to shine a light on class issues of his day and the changes he hoped to see made. Many readers are familiar with Gulliver’s Travels, Swift’s four-part travelogue of ship’s surgeon Lemuel Gulliver.

Many Americans mistakenly believe it to be a children’s book. It is anything but.

The most popular saga in Gulliver’s Travels is the first of four … when Gulliver ends up shipwrecked on the shores of the land of Lilliput. He awakens to find himself tied down on the beach by Lilliputians. To his shock, his captors all are under 6 inches tall. After giving assurances of his good behavior, Gulliver is given a residence in Lilliput and becomes a favorite of the Royal Court.

He soon discovers the Lilliputians are petty and foolish people who are preoccupied with trivial matters. For example, a political rift exists in the Court over which end of an egg should be broken. The conflict is divided between the “small-enders” and “big-enders.” The allegory is a back-handed rebuke of the infantile nature of the British royal court.

Later, Gulliver agrees to assist the Lilliputians to subdue the neighboring island nation of Blefescu3 by stealing their war fleet. However, he refuses to reduce Blefescu to a province of Lilliput, which displeases the King and court. Gulliver is charged with treason, convicted and sentenced to be blinded. With the assistance of a friend, he eventually escapes to Blefuscu.

The parallel Swift draws between the Lilliputians' small stature and small-mindedness is unmistakable. Tidbits of sarcasm and silliness are scattered throughout; the funniest bit is when a drunken Gulliver puts out a fire in the capital by urinating on the blaze.

“A Modest Proposal”

As light-hearted and fun as is Gulliver's Travels, Swift takes an adversely dark tone with his satirical essay “A Modest Proposal.”

Swift, an Anglo-Irish cleric, was appalled by the state of Ireland early in the 18th century. The country was desperately poor and its populace bordered on starvation. At that time, Ireland was a separate kingdom ruled by King George II of Britain4. The monarchy and Anglo-Irish landowners paid little heed to the Irish plight, and the Vatican had virtually no power to help.

Swift’s efforts to aid the Irish fell on deaf ears. So in 1729, he anonymously penned and published an essay entitled “A Modest Proposal For Preventing the Children of Poor People From Being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country, and For Making them Beneficial to the Publick.”

The essay argues that the impoverished Irish might ease their economic troubles by selling their babies as food to rich gentlemen and ladies.

This shocking, hyperbolic proposal mocked heartless attitudes towards the poor Catholics (i.e., "Papists") as well as British policy toward the Irish in general.

The essay argues that the impoverished Irish might ease their economic troubles by selling their babies as food to rich gentlemen and ladies.

“A Modest Proposal” is widely held to be one of the greatest examples of sustained irony in the history of the English language. Much of its shock value derives from its sober, pragmatic approach: it is written in straight-faced, logical language, so the reader is unprepared for the surprise of Swift's grisly solution.

Swift goes to great lengths to support his argument, including a list of possible preparation styles for the babies …

"A young healthy child well nursed, is, at a year old, a most delicious nourishing and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee, or a ragout.” – “A Modest Proposal” (Jonathan Swift)

He also uses algebraic calculations to show the financial benefits of his suggestion. The serious tone illustrates extreme irony and accents the absurdity of his proposal. Even the title is “deliciously” ironic: the proposal is anything but modest.

Swift's essay created a backlash after its publication. The work was aimed at the aristocracy and they responded in turn. But aside from the shock, little progress was made until the Vatican began expanding its landholdings in Ireland several decades later.

Mark Twain: American Gospel

Across the ocean, no one matches the exquisite parodic gaze of Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known as Mark Twain. He was, and remains today, the quintessential American literary master.

Twain catapulted to success with his short story, The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, a tale that parodied myths and legends of frontier life that resonated with the nation.

Jumping Frog, like many of Twain’s spoofs, is pure whimsy. No author of any era used homespun dialects and idiomatic expressions as adroitly as Twain. Jumping Frog features folksy, rustic dialog, often punctuated by understatement and crackerjack allusions5 (see: Dan’l Webster below). The reader can feel the trail dust and smell the smoke-filled taverns drift up off the page.

Twain uses a frame6 story as a jump-off to the tale of a frontiersman named Jim Smiley. Smiley is a prolific gambler who will bet on anything. He owns several feeble-looking animals but trains them to be fierce fighters and racers, including a sickly mare and a motley bulldog named Andrew Jackson. Unsuspecting patrons are more than willing to bet against these pitiful animals, but Smiley’s grift always wins in the end.

Among Smiley’s stable of deplorables is a frog named Dan’l Webster (a not-so-subtle allusion to former U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster, who viewed slavery as a matter of historical reality rather than a moral principle). Smiley trains the amphibian to be a champion jumper, and pits him against any gullible greenhorn.

One day a stranger comes to town, and Smiley goads him into a $40 bet in a jumping contest. The stranger doesn’t own a frog, but Smiley quickly agrees to fetch a rival jumper from a local pond to secure the bet.

While Smiley is gone frog-gigging, the stranger opens Dan’l Webster’s mouth and pours in a bag of quail shot, stuffing his gut with lead pellets. When Smiley returns with a contestant frog, the contest is on. The stranger’s new frog goes first and jumps a fair distance.

But when prompted, Dan’l Webster is immobilized, hopelessly anchored to the floor with his hefty burden. The stranger leaves with $40 in his pocket and Smiley is left behind with a look of incredulity on his face.

No American satirist, then or now, outpaces Mark Twain. He dealt with race, economics, politics, culture and human nature in an era where there were few sacred cows or deference to fragile feelings. No person immersed in power and corruption, or mired in stupidity, was spared from his acerbic wit and verbal harpoons.

Twain later toured the world and performed his comedic material long before George Carlin or Dave Chappelle. And, of course, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and its sequel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, are canonized as American literary gospel.

Kurt Vonnegut: Slaughterhouse Five

“So it goes.”

As a comic conscience, there is none like Mark Twain, and we can only hope for successive satirists worthy to be called his heir. But Kurt Vonnegut came close.

There are lots of anti-war satire novels still in circulation, among them Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 and Richard Hooker’s (nee: Dr. H. Richard Hornburger) M*A*S*H. All funny, characteristically dark and parodic. But none is as quirky or idiosyncratic as Vonnegut’s tour-de-force, Slaughterhouse Five (1969).

Centering on the fire-bombing of Dresden, Germany by the Allies during WWII, Vonnegut’s most famous work stars the time-traveling Billy Pilgrim as a fatalistic soldier who refuses to fight and is captured by the Germans, only to be bombed by his own side.

A peculiar and often hilarious novella, Slaughterhouse-Five uses postmodern self-consciousness and light comic relief to throw a spotlight on the murderous inhumanity of war. It is a semi-autobiographical work, as Vonnegut himself was captured at the Battle of the Bulge and was a POW in Dresden. He bore personal witness to the Dresden carnage, which history has viewed as barbaric and strategically unnecessary. The sadness often shows in the text.

But so do his quirky, oddball sensibilities. Situational and verbal ironies are brief but thick (The detached phrase “so it goes” follows the discovery of every death). Vonnegut’s dry but witty understated tone makes Slaughterhouse Five a curious dichotomy between humor and outrage. At any given moment, the reader doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

And then there’s Tralfamadore. At one point, Pilgrim is kidnapped by extraterrestrial aliens and placed in a zoo on the planet of Tralfamadore. The Tralfamadorians are described as single-eyed creatures resembling toilet plungers.

They are a curious lot, and Billy learns from his captors that past, present and future all exist simultaneously. Thus there is a fatalistic message in Tralfamadorian philosophy: each moment in life is no more important or permanent than any of the others. For instance, Billy’s ability to time travel means that he has witnessed his own birth, his own death, and every life moment in between countless times.

Postscript: Humor is Hard

Writing is hard. Writing “funny” is doubly hard, especially since the trigger that evokes laughter is a physiological enigma. The funny bone doesn’t show up in X-rays.

Today’s humor is mostly performative, a combination of visual and auditory stimuli that produces the right dopamine hit. Stand-up comics have a keen sense of this stimulant. But it usually takes years to hone their craft.

Satire is an effective rhetorical tool because it is designed to make criticism approachable through humor.

Cinematic satire is acted out, relying on the skills and prowess of the screenwriters, performers and directors. Dr. Strangelove (1964) and Network (1976) are cinematic satires that contain the requisite intellectual capital to qualify as classics. Parodies have worked well … witness the Scary Movie series, the National Lampoon Vacation franchise, and anything written and directed by comic genius Mel Brooks.

But the written word relies on a special combination of knowledge, context, analysis, synthesis and judgment. You know, thinking. And thinking is something humans don’t do very well in the 21st century. But it is much needed in a time of such relentless antipathy and frayed nerves. Satire is an effective rhetorical tool because it is designed to make criticism approachable through humor.

Besides, we all could use a little laugh now and then.

##

Jim Geschke was inducted into the prestigious Marquis Who’s Who Registry in 2021.

Thomas Becket, also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, was the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162-1170. He engaged in conflict with Henry II, King of England, over the rights and privileges of the Church and was murdered by followers of the king in Canterbury Cathedral. He is venerated as a saint and martyr by the Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion. Soon after his death, Becket was canonized by Pope Alexander III.

Heroic couplets: consecutive rhyming lines (ex. a-a, b-b, c-c, etc.)

The parallels between Lilliput/Blefescu and England/France are readily apparent

It should be noted that the Anglican church was/is Protestant, while Ireland at the time was made up of predominantly Catholic peasants.

Allusion: references to persons, places or things from the past

The story begins with an unnamed narrator who tracks down a man named Simon Wheeler in a tavern in California. The narrator asks Wheeler if he knows a man named Leonidas W. Smiley. But instead Wheeler launches into a tale of another man with a similar name, Jim Smiley. Thus begins the tale of the Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.

Look forward to reading this when time permits; wanted to say hi. Hope you're well?!

George Carlin is my favorite stand-up comic. He could really slice up the foibles of American society.

CardiffRob