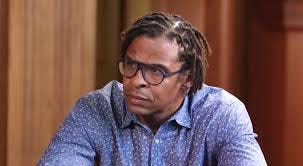

The rise, fall and redemption of Roland Fryer

From childhood abandonment ... to celebrated scholar ... to being "canceled" by Harvard. Now he's back, and challenging the odds again.

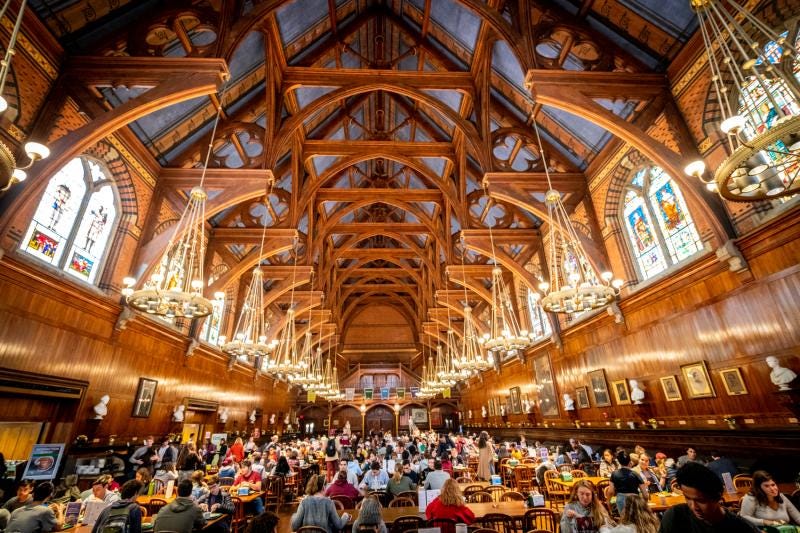

It is likely Roland Fryer had never seen a vine of ivy before arriving at Harvard in 2003 … unless it was the poison kind. He had never tasted the dryness of Amontillado Sherry, or heard the synchronous harmony of a Haydn composition — or any chamber music for that matter — as he did that first week while dining with the Society of Fellows at Annenberg Hall.

The air was different, too. It was thick. And regal. It smelled like … aristocracy.

The world Fryer came from was shatteringly different. Growing up between hard neighborhoods in Daytona Beach, FL and Lewisville, TX, he had sniffed the inside of a police car … heard the rattle of gunshots and screeching tires from a driveby shooting … and seen real blood run in a gutter. His arrival at Cambridge wasn’t just culture shock — Ivy League gentility was more of an illusion, or an alternate reality.

Based on every statistic and stereotype, Fryer should not have become what he became. Nothing about “Hah-vad” told him “I belong.” Not the rolling campus greens, the immense collection within its 93 libraries, or the storied history within its wood-grained halls. He was so socially awkward he actually read Emily Post columns on how to behave in polite society.

But his brilliant mind belonged. That mind empowered him to produce groundbreaking work on race, equality and education and propelled him to the top of his profession. For more than a decade, Fryer represented what Harvard’s elite proudly celebrated — a brilliant young black man of boldness, scholarship and moral courage.

That is until his speaking “truth to power” ran against conformative thinking. When he did, Harvard’s elite turned on him.

More on that below.

The Unlikely Genius

Young Roland Fryer was abandoned by his biological parents before reaching his teen years. He grew up with what he called his “drug family,” a band of young street criminals and crack dealers. Most now are either dead or incarcerated. (Note: Fryer himself did not deal drugs. But he did hustle fake purses out of a car trunk).

Not surprisingly, he wasn’t a very good student. But he excelled at athletics, which became his ticket to escape street life.

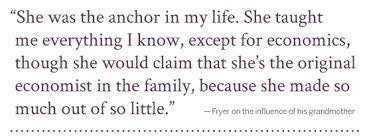

His “North Star” was his grandmother, Farrise, whom he credits for saving him from becoming just another urban statistic. It was more than her gentle hand guiding the reckless boy — Farrise recognized young Roland’s instinctual curiosity and instilled a fierce work ethic to help him fully realize his gifts.

His basketball skills were good enough to earn an athletic scholarship from the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA). But he never played a single game at UTA.

Instead, serendipity was on his side.

As a freshman Fryer enrolled in an economics class … 8 a.m. Mondays and Wednesdays. He immediately was mesmerized by the world of numbers and probabilities. Recognizing his enthusiasm and unique gifts, the Econ professor supported him, and with the help of one of UTA’s deans Fryer’s scholarship was switched to an academic award. He excelled in his studies and graduated Magna cum Laude in just 2 1/2 years.

From UTA he enrolled in the economics Ph.D. program at Penn State. He eventually earned his doctorate from PSU in 2002, but already by 2001, he had obtained a post-doc position at the University of Chicago — one of the top Econ schools in the country. At UC he was sponsored by Nobel laureate Jim Heckman (Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, 2000) and co-authored papers with economist Steven Levitt (later of Freakonomics fame).

Then it was on to Harvard.

Harvard’s “Rock Star”

Though he was on unfamiliar ground, Fryer excelled. It didn’t take long for Harvard to recognize the jewel they found.

At 30, he became the youngest black tenured professor in Harvard’s history. At 34, he won a John Bates Clark Medal, given to an economist in America under 40 who is judged to have made the most significant contribution to economic thought and knowledge.

Fryer’s curriculum vitae (CV) is extraordinary:

Author or co-author of 50-plus academic papers distributed by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), including the AERA, QJE, JPE, REStat, and JPubEcon.

Received the MacArthur Fellowship in 2011 (commonly known as the MacArthur “Genius Awards”)

Research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research, and a member of the NBER Economics of Education (EE) and Labor Studies (LS) programs.

John A Paulsen Fellow at the Manhattan Institute

A fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

In the decorous world of Academia and Economics, Roland Fryer was a rock star.

EdLabs

From the start, Fryer’s focus was on education. Systematically, he set out to understand and quantify the problem of the black achievement gap in America, hoping that hard, scientific data would shed light on the most effective ways to narrow the gap.

In 2008, Fyer set up the Harvard Education Innovation Lab (or EdLabs), which employed Harvard graduate students, post-docs, and alums. At one point at least 20 people worked at EdLabs. It was a major operation, with office space just off campus.

Fryer demanded procedural rigor and strict protocols at EdLabs. Biases were rooted out. Everything was crafted to uncover truth in data, or as Fryer would say, “take us where the numbers take us.”

Given its rigid adherence to scientific methods, EdLabs would seem a stifling, socially constricting place to work. Quite the opposite. Fryer was a charming and charismatic figure whose off-campus hobby was stand-up comedy. His affable nature fostered a collegial working environment. He maintained close-knit relationships with many of his researchers.

It was that informality that would later get him into trouble with Harvard’s elites.

Investing in “Human Capital”

Fryer often called his work an investment in “human capital.” He focused on studying human problems and finding human solutions. Changing the human odds using numbers ... trying to make his own path less exceptional … trying to increase the probability that black kids could change their trajectory in society using education as the lever.

His research was innovative and sometimes controversial.

“Acting White”

Fryer also looked at the issue of “Acting White” – an unconventional project that later became one of his most-cited works. “Acting white” was a label sometimes used by scholars to characterize minority students who were unpopular among their peers because they were academic achievers.

It seemed a frivolous concept for research. But then-Senator Barrack Obama found it important enough to mention it in his keynote address at the 2004 Democratic National Convention. Fryer used older data sets plus his own study of private and public schools. Though it had been assumed that negative attitudes were holding back exceptional black students, Fryer found inconclusive evidence that it was true.

Harlem Children’s Zone

Fryer also studied the chartered schools run as part of the Harlem Children’s Zone (HCZ) project. Those schools had been highly successful, and Fryer wanted to answer a) whether the strong student performance could be explained by the quality of the schools alone, or by the combination of the schooling with the web of community support around them, and b) could the HCZ model be replicated elsewhere?

The study found, not surprisingly, that the quality of the schools and the community support made a dynamic equation in closing achievement gaps. Shortly after, in 2010, the Obama administration carved out federal funding for the HCZ model to be piloted in other major cities.

The “Lethal Force” problem

With the increased attention being given to police shootings in the mid-2010s, specifically the cases of Michael Brown and Freddie Gray, Fryer initiated a study to determine the degree to which the use of lethal force might reflect racial biases. He assumed there were — the question was by how much.

Fryer’s researchers obtained data on police shooting incidents from 18 law enforcement agencies across the country,1 each for some subset of the years between 2000 and 2015 … a total of more than 1,500 cases. To help ensure accuracy, Fryer had every file read by two researchers, acting independently, and then checked whether both coded the same for the given variables.

Fryer’s key finding was surprising. It shocked him. He wrote:

“… we find, after controlling for suspect demographics, officer demographics, encounter characteristics, suspect weapon and year fixed effects, that blacks are 27.4 percent less likely to be shot at by police relative to non-black, non-Hispanics.”

Similarly, Fryer examined the impact of race on whether the officer or the suspect fired their weapon first. Taking all factors into account, he found in his regression analysis that an officer firing first in the encounter was 46 percent less likely when the suspect was Black, and 44 percent less likely if the suspect was Hispanic.2

It was NOT what he expected. But the numbers didn’t lie.

Early in 2016, Fryer shared a working paper with colleagues and selected reviewers that stated although minority suspects were more likely to experience lower-level uses of physical force than white suspects, such as “roughing up” against a police car, the deadly force assertions simply weren’t true.

In fact, he had found the opposite.

Harvard Orthodoxy: “Veritas?”

Privately, colleagues encouraged him not to publish. Many warned him it would be career suicide. Fryer forged ahead anyway. He believed in the truth. And he paid dearly for it.

The prevailing orthodoxy at Harvard, and in Academia in general, dictated that because minorities historically were victims of social injustices, black suspects were disproportionally victims of fatal police shootings. It was accepted as fact. Nothing could detract from the narrative, regardless of efficacy.

Fryer's paper eventually was published in the Journal of Political Economy in 2019. But by that time it already had shaken the Academic world, the media and Harvard itself.

“People lose their minds when they don’t like the results.” — Roland Fryer on his controversial work.

“CANCELLED”

It was no secret that the police study rankled Harvard leadership. What followed became what is a now-familiar plot … to purge non-conformists (i.e. “canceling”).

Fryer had become a target.

In March 2018, Harvard launched an investigation into Title IX complaints against him alleging sexual harassment.

Harvard confirmed that its Office for Dispute Resolution (ODR) received complaints from a former assistant who worked in EdLabs. His former personal assistant — some say with an axe to grind — accused him of sexual harassment.

The investigation found that he hadn’t sexually propositioned or touched anyone; his misconduct amounted to some flirtatious text and email messages and a few off-color jokes. The ODR recommended workplace sensitivity training.

This recommendation was passed on to a panel of Harvard tenured faculty, including Dean of Faculty Claudine Gay and Lawrence D. Bobo. Fryer’s work — especially the fatal police shooting study — didn’t sit well with them. This was a period when the #MeToo movement was in full force, and the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) apparatus was firmly entrenched at Harvard. Gay and Bobo were two of DEI’s most ardent champions.

Gay and Bobo pushed for much harsher punishment. In July 2019, the faculty panel led by Gay suspended Fryer from Harvard for two years without pay, stating he "engaged in unwanted sexual conduct toward several individuals" and "exhibited a pattern of behavior that failed to meet expectations of conduct within our community."

Gay, whose short and ignominious term as President of Harvard became nationwide news in late 2023, unsuccessfully lobbied for Fryer to be stripped of his tenure. She couldn’t … no one had lost tenure at Harvard in more than 100 years.

Regardless, his career was in tatters. All for some ‘off-color” remarks.

In a letter to The New York Times later that month, Fryer expressed regret for having a collegial atmosphere at EdLabs but denied bullying, retaliating against employees, or ever making sexual advances to any employee.

Aftermath and Redemption

Fryer returned to Harvard after his two-year unpaid sabbatical in July 2021. EdLabs was closed, but the charismatic Econ whiz picked up where he left off, conducting research to help design policies that can increase economic and educational opportunities in America. He’s also back in the classroom, teaching both undergraduate and graduate courses.

During his absence from Harvard, he and venture capitalist Bill Helman co-founded Equal Opportunity Ventures (EOV). The company offers young entrepreneurs with seed funding, strategic support, and access to a team of advisors on how to build successful businesses while maximizing social impact.

Today, Fryer is an oft-requested speaker at conferences and symposia and is in high demand as a podcast guest.

The redemption he has found is simple: still audaciously seeking the truth.

“Roland Fryer is the most gifted economist of his generation. Not the most gifted black economist of his generation, but the most gifted economist of his generation. Period … To do the kind of work Roland does, you have to be more than brilliant. You have to be fearless.” — Glenn Loury, Economist, Brown University

Feb. 2024 Interview with The Free Press

###

Jim Geschke was inducted into the prestigious Marquis Who’s Who Registry in 2021.

Most of the agencies were police departments in California, Texas and Florida

This part of the study was confined to the Houston area only.

Jim,

Thank you for writing this powerful story.

It is a cautionary tale of vital importance

and relevance to all our lives.

I am in awe of Roland Fryer's courageous devotion to truth

and his ultimate triumph over those who canceled him for it.

He shows us how to withstand the misuse of power

wielded by politics against science.

In my field, psychology, politics has taken over.

If I were still in clinical practice,

I would lose my license for my promulgating scientific theories

that refute progressive orthodoxy.

But to quote Galileo: "Nevertheless, it moves."

Quite a guy! Glad it worked out as it should.